████████╗██╗ ██╗███████╗ ████╗██╗ ██╗███╗ ██╗██╗ ██████╗ ██████╗

╚══██╔══╝██║ ██║██╔════╝ ╚██╔╝██║ ██║████╗ ██║██║██╔═══██╗██╔══██╗

██║ ███████║█████╗ ██║ ██║ ██║██╔███╔██║██║██║ ██║██████╔╝

██║ ██╔══██║██╔══╝ ██╗ ██║ ██║ ██║██║╚██╝██║██║██║ ██║██╔══██╗

██║ ██║ ██║███████╗ ██████╔╝ ╚██████╔╝██║ ╚████║██║╚██████╔╝██║ ██║

╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═══╝╚═╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝

██████╗ ██╗ ██╗██╗██████╗ ███████╗ ████████╗ ██████╗

██╔════╝ ██║ ██║██║██╔══██╗██╔════╝ ╚══██╔══╝██╔═══██╗

██║ ███╗██║ ██║██║██║ ██║█████╗ ██║ ██║ ██║

██║ ██║██║ ██║██║██║ ██║██╔══╝ ██║ ██║ ██║

╚██████╔╝╚██████╔╝██║██████╔╝███████╗ ██║ ╚██████╔╝

╚═════╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝╚═════╝ ╚══════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═════╝

██████╗ ██████╗ ███╗ ███╗██████╗ ██╗███╗ ██╗ ████╗ ████████╗ ██████╗ ██████╗ ██╗ ████╗ ██╗

██╔════╝██╔═══██╗████╗ ████║██╔══██╗██║████╗ ██║██╔═██╗╚══██╔══╝██╔═══██╗██╔══██╗██║██╔═██╗██║

██║ ██║ ██║██╔████╔██║██████╔╝██║██╔███╔██║██████║ ██║ ██║ ██║██████╔╝██║██████║██║

██║ ██║ ██║██║╚██╔╝██║██╔══██╗██║██║╚██╝██║██║ ██║ ██║ ██║ ██║██╔══██╗██║██║ ██║██║

╚██████╗╚██████╔╝██║ ╚═╝ ██║██████╔╝██║██║ ╚████║██║ ██║ ██║ ╚██████╔╝██║ ██║██║██║ ██║███████╗

╚═════╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═════╝ ╚═╝╚═╝ ╚═══╝╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═╝╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════╝

██████╗██╗ ██╗███████╗███╗ ███╗██╗███████╗████████╗██████╗ ██╗ ██╗

██╔════╝██║ ██║██╔════╝████╗ ████║██║██╔════╝╚══██╔══╝██╔══██╗╚██╗ ██╔╝

██║ ███████║█████╗ ██╔████╔██║██║███████╗ ██║ ██████╔╝ ╚████╔╝

██║ ██╔══██║██╔══╝ ██║╚██╔╝██║██║╚════██║ ██║ ██╔══██╗ ╚██╔╝

╚██████╗██║ ██║███████╗██║ ╚═╝ ██║██║███████║ ██║ ██║ ██║ ██║

╚═════╝╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════╝╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═╝╚══════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝

// OLIVER SERANG

// NSF CAREER GRANT #1845465

The Junior Guide to Combinatorial Chemistry by Oliver Serang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Thank you very much to E for the nice illustrations.

Feel free to use it to teach chemistry, combinatorics, and programming to your children!

ELEMENTS AND ATOMS

Everything in our world is made up of elements. The smallest building block of each element is an atom.

PROTONS, NEUTRONS, AND ELECTRONS

Each atom has a nucleus. The nucleus is the center composed

of protons and neutrons. Protons are large and are drawn with

a + symbol on them because they are positively

charged. Neutrons are large and have no charge. Atoms also have

an electrom cloud, with little electrons orbiting the

nucleus. Electrons are small and are drawn with a -

symbol. PIC: example atoms from a few elements.

WEIGHT AND MASS

Each atom of an element has a particular heft. Elements with a higher atomic number have more protons in their nucleus, which makes it more dense. And if the atom is an isotope with more neutrons in its nucleus, then it also becomes more dense.

We can think of this as some atoms being heavier than others. But weight isn't a precise term: Consider that something weighing 100lbs on earth will weigh only 16.54lbs on the moon; this is because the earth is larger and has a stronger gravitational force. Since we want to talk about each atom in a way that doesn't depend on where we measure it, instead of weight, we talk about mass. Mass is the amount of matter in something. The mass of an atom is roughly the sum of the masses of the protons, neutrons, and electrons that make up the atom (this estimate is slightly incorrect, as we'll see because of relativity).

AN ATOM'S IDENTITY AND ITS ATOMIC NUMBER

An atom's atomic number tells who it is. This atomic number is the number of protons in its nucleus. Hydrogen always has 1 proton in its nucleus, and so it has an atomic number of 1. Helium always has 2 protons in its nucleus, and so its atomic number is 2.

ATOMIC SYMBOLS AND THE PERIODIC TABLE

We write elements so often that we abbreviate their names to save time. Hydrogen is abbreviated to

We draw these elements in the periodic table. If we go left to right and then top to bottom, it counts off the atomic number of each element.

- What is the atomic symbol for tin?

- What is the atomic symbol for lead?

- What is the atomic number of polonium?

- What is the atomic number of mercury?

- What is the atomic number of

I ? - What is the atomic number of

Cu ? - What is the atomic mass of xenon?

- What is the atomic mass of zinc?

- What is the atomic mass of

Ca ? - What is the atomic mass of

Ir ? - What is the atomic mass of

Fe ?

IONS AND ISOTOPES

Atoms usually have the same number of electrons as protons; however, the number of electrons can vary. For example,

Atoms also usually have similar numbers of neutrons as protons in their nucleus, but the number of neutrons we'd expect can vary. For instance,

How many protons, neutrons, and electrons are in each atom?

Ag : Atomic number = 47, so 47 protons. The 107 mass (by rounding) means that there are 60 neutrons missing. Note thatAg usually has mass (by rounding) of 107.868 ≅ 108, so silver usually has 1 more neutron than the isotope we see here. The charge of this silver atom is -2, meaning it has 2 more electrons than its atomic number (note that electrons have a negative charge, so 2 electrons gives a -2 charge), so it has 47+2 = 49 electrons.Hg Ti Fe Cl Xe

CODE: BASIC PYTHON

You can run the code by clicking the green button on the left (you can also run the code by typing the [Shift] and [Enter] keys at the same time. After editing, you can restore the original code using the white button on the right. If a piece of code runs for too long, you can click the red stop button or reload this page.

- Modify this code so that it prints your name!

CODE: IF-ELSE STATEMENTS

- Modify this code so that it prints "hello Kryptonian" only if the name is Clark Kent. Otherwise, print "greetings, earthling" (no need to worry about printing the quotation marks).

CODE: ARITHMETIC

- Modify this code so that it computes the number of seconds in the month of January.

CODE: LOOPS

Modify this code so that it prints integers starting at 0 and <16.

- Modify this code so that it prints your name 16 times.

- Modify this code so that it prints your name 30 times.

CODE: LOOPS

- Modify this code so that it sums 0+1+2+3+4+5+6+7+8+9+10+11+12+13+14+15.

CODE: LOOPS

- Modify this code so that it uses loops to compute the number of seconds in one hour. Note that your code might take a little bit of time to run. Do not use the multiplication operator, *.

CODE: LISTS

Modify this code so that it makes the list [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and computes the sum. Then modify the code so that it makes a list of the numbers starting at 0 and <128.

CODE: LIST COMPREHENSION

- Modify this code so that it sums the even numbers <128.

- Modify this code so that it sums the numbers <128 that are divisible by 3.

- Modify this code so that it sums the numbers <128 that are even or divisible by 3.

CODE: DICTIONARIES

Dictionaries are used to turn keys into values. Here, the keys are names and the values are ages.

- Edit the code so that your name is mapped to your age.

- Lookup the age of Mary and print her age.

CODE: FUNCTIONS

Functions let us avoid repeating ourselves. Functions let us avoid repeating ourselves...

- Modify the code so that print_meme_text('AESTHETIC') prints

AESTHETIC ESTHETIC STHETIC THETIC HETIC ETIC TIC IC C

Note that if you'd like to print 'abc' without printing a newline character, you'd call print('abc', end='').

CODE: THE 12 DAYS OF PYTHON

Use functions and loops to print the lyrics to the 12 days of python!

CODE: ESTIMATING THE MASS OF AN ATOM

EXERCISE: ESTIMATING ATOMIC MASSES

Look up the atomic number for these elements and modify and use the python code above to estimate the mass of each atom. How do your estimates compare to the masses listed on the periodic table?

Ag From the exercise above, we have 47 protons, 107-47=60 neutrons and 47+2=49 electrons. In the terminal above, we call estimate_atomic_mass(47, 60, 49), which returns 107.88286592. Note that this is higher than the actual mass ofAg , which is 106.905097.Hg Ti Fe Cl Xe

MASS DEFECT

The difference between our estimate of the atomic mass (by summing the protons, neutrons, and electrons) and the actual atomic mass is called the "mass defect" (don't let the name fool you-- nothing is wrong here, mass defect is a perfectly natural phenomenon, which we'll uncover!). This mass defect is a measure of how much energy it would take to break apart the nucleus of the atom into those parts.

The estimated mass for

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AT REST?

We usually think of ourselves as at rest when we're sitting on earth without moving; however, the greatest rest can be seen by floating free in space far from any planet. In this place, you are not only at rest, there are no external forces acting on you. If you dropped a ball in space, it would simply float next to you. In contrast, on earth a dropped ball would fall rather than floating next to you.

If you fell from a roof and dropped a ball as you did so, you would both fall in the same way. In this manner, it would seem to float next to you. Relative to the earth, the ball would be falling (as you would be); however, relative to you, the ball would be floating and at rest.

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: WITHOUT LANDMARKS, MOTION IS RELATIVE

On a bus you can feel if it accelerates or if it slows; however, when it is moving forward at a constant speed, it exerts no force on you. For this reason, you can feel nothing.

If you were floating in space, you could feel if someone pushed off of you or pulled you, but you wouldn't be able to feel your velocity. So from a certain perspective, you would be seen to be at rest, even though you are moving. Likewise, if you passed by someone else, without external landmarks (such as stars or planets), it would be impossible for either of you to determine which of you is moving. Moving relative to what? Perhaps you are stationary and the other person is moving, or perhaps they are stationary and you are moving. What you can determine is that you are moving relative to each another.

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: IS IT GRAVITY OR ACCELERATION AFFECTING YOU?

In a similar manner, consider this thought experiment: You wake up in a rocket ship with no windows. You have a ball, and when you drop it, it falls to the ground. Perhaps you are on earth? Or perhaps you are in the rocket ship as it accelerates forward, forcing the ball toward the bottom of the ship? The fact is that you cannot distinguish these scenarios.

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: ACCELERATION BENDS WATER AND LIGHT DOWNWARD

If you had a water hose pointed horizontal in this rocketship (where the rockets are shooting out from the beneath the floor and the rocket is moving toward your head), then as the water came out of the hose, the floor of the ship would accelerate upward toward it. In this manner, the water of the hose would bend down toward the floor. This would be indistinguishable from a scenario where the ship were sitting on earth without moving; in this scenario, the water from the hose would likewise bend down toward the floor of the ship.

Interestingly, if the ship were accelerating quickly enough, the same would be true for a beam of light: as the ship accelerated forward, the floor would accelerate toward the beam of light, and so as it traveled further, it would bend toward the floor.

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: THE DOPPLER AFFECT AND RED/BLUE SHIFT

If a train speeds toward you and sounds its horn, the sound of the horn will go up in pitch (i.e., a higher frequency or shorter wavelength) as it nears you. This is because the sound waves are compressed, squished forward due to the speed of the train. And after it passes you, the train speeding away, the sound of the horn will go down in pitch (i.e., a lower frequency or longer wavelength), because it speeds away.

The same is true for waves of light: If an object glows yellow and it accelerates toward you, the waves of light will bunch up from your perspective, causing the glow to appear to you as a higher frequency blue instead of yellow. Likewise, if the object accelerates away from you, then the waves of light will stretch out from your perspective, causing the glow to appear to you as a lower frequency red instead of yellow. These phenomena are called blue shift and red shift, respectively.

And if at 12:00 noon you were to speed away from a clock tower at nearly the speed of light, the light reflected from the clock tower rarely catch up with you. In this manner, several minutes after you raced away from the clock tower, you would still be seeing light that had reflected off of the tower when the time was still roughly 12:00 noon. So time would seem to slow down for you as you moved so quickly.

THE THEORY OF RELATIVITY: MASS AND ENERGY EQUIVALENCE

Consider yourself sitting at rest inside a rocket ship with a window. A yellow lightbulb is sitting in space far ahead of you. We will consider two scenarios. In both, you will only observe, and so you will not influence the lightbulb.

In scenario (A), you see the yellow lightbulb blink on briefly, and then afterward, you accelerate toward it in your rocket ship. Relative to you, the lightbulb has gained kinetic energy but it has lost the energy from the yellow light emission.

In scenario (B), you first accelerate toward the lightbulb, and it blinks on briefly while you are accelerating. Because of the blue shift, you see the color as blue rather than yellow. Relative to you, the lightbulb has gained kinetic energy but it has lost the energy from the blue light emission.

Because you don't influence the lightbulb, its net energy is

the same in both scenarios. But yellow light has less energy

than blue light, and so in scenario (B) it loses more

energy; thus, the kinetic energy gained in B must be

higher than the kinetic energy gained in (A) so that the

total energy of the lightbulb in both (A) and (B)

are identical. Since the end velocity of the lightbulb are the

same in both (A) and (B), then the only way for

the kinetic energy gained in (B) to be higher than the

kinetic energy gained in (A) would be for the mass of the

lightbulb to decrease as a result of the light emitted first. In

this manner, the energy of the light can be seen to consume the

mass in scenario (A), and so the velocity of the

lightbulb grants it lower kinetic energy. From this, we get the

mass-energy equivalence equation: E = m c2.

ACTIVITY: MEASURING ENERGY IN RED AND BLUE LIGHT

Place a 60W light bulb with blue filter above a thermometer. Start the thermometer in a refridgerator so that it is cold. After one hour, record the temperature of the thermometer after it has absorbed blue light. Repeat with a cold thermometer using red light. What do you find? Why? What does this have to do with relativity?

CONVERTING: BRITISH POUND STERLING TO U.S. DOLLARS

If the exchange rate sets the Great British Pound Sterling (GBP) as worth 1.4 U.S. Dollars (USD), edit the following python script to convert 17 GBP to USD.

CONVERTING: MASS DEFECT TO ENERGY IN MEGA ELECTRON VOLTS

The exchange rate between energy, measured in mega electron

volts (MeV), and atomic mass units is 931.5 MeV per atomic mass unit. Edit

the following python script to convert the mass defect

of

COMPOUNDS

Multiple elements can be combined to form a compound. Water

is a compound made of 2 hydrogens and 1 oxygen. This is

written using the chemical formula for the compound,

We can estimate the mass of a compound as roughly the sum of the masses of the elements from which it is built. For example, the mass of water is roughly 2×1.008u + 15.999u = 18.015u. The mass defect for compounds is usually less pronounced than the mass defect when computing atomic masses. This is because the nuclear force that holds together the nucleus is far stronger than the bonds holding together compounds; because the energy of the bonds is less, than the mass defect from that bonding energy is less pronounced.

CODE: ESTIMATING THE MASS OF A COMPOUND

We can estimate the mass of a compound by summing the atomic masses of the elements in it:

Notice that the molecular mass of water is roughly 18.015. Our estimate is very accurate (i.e., the mass defect is much more muted). Because of the mass-energy equivalence we saw when studying relativity, we will overestimate the true molecular mass because of the binding energy in the compound. This is because far less energy is required to break apart a compound than to break apart the nucleus of an atom. In turn, this is why nuclear reactions (which split or fuse atoms) produce far more energy than conventional chemical reactions (which break or create chemical bonds).

EXERCISE: ESTIMATING THE MASSES OF COMPOUNDS

Modify and use the python code above to estimate the mass of each compound. For what is each compound known?

- Water

H2O1 ≅ 18.01528u - Ammonia

N1H3 - Hydrogen Peroxide

H2O2 - Methane

C1H4 - Glucose

C6H12O6 - Citric Acid

C6H8O7 - Lycopene

C40H56 - Baking soda

Na1H1C1O3 - Epsom salt

Mg1S1O4

ACTIVITY: CHOOSING AN ITEM FROM ITS MASS

Use a small ball of clay and a large ball of foam (such as a stress ball).

- Lift the foam ball and clay balls. Which one is heavier? How is this possible given their sizes?

- Close your eyes and have someone else place one ball in a brown paper bag. By only lifting the bag (do not try to feel its contents!), can you figure out which ball is in the bag using only its weight?

- If you had two foam balls and two clay balls, could you distinguish any pair (e.g., foam+foam, clay+foam, or clay+clay) using only the weight of the bag?

- In the above question, why do we not distinguish clay+foam from foam+clay?

EXERCISE: CHOOSING ITEMS FROM THEIR PRICES

Consider these yummy desserts-- each has a different cost.

| DESSERT | PRICE | |

|---|---|---|

| Mint chocolate chip ice cream |  |

$10 |

| Birthday cake |  |

$13 |

| Soft-serve frozen yogurt |  |

$9 |

| Pumpkin pie |  |

$8 |

| Smore |  |

$6 |

| Orange Jello |  |

$3 |

| Grape soda |  |

$2 |

| Blueberries |  |

$5 |

| Cupcake |  |

$6 |

| Boston cream pie |  |

$23 |

| Strawberry |  |

$7 |

| M&M cookie |  |

$11 |

- How much would 1×

cost?

cost?

- How much would

+

+ cost?

cost?

- How much would 2×

+

+ cost?

cost?

- How much would 3×

+5×

+5× cost?

cost?

- How much would 3×

+

+ +

+ cost?

cost?

- How much would

cost?

cost?

- Can you find another menu item that would be worth the same amount as in the previous question?

- How much would 10×

cost?

cost?

- Can you find menu choices that would be worth the same amount as in the previous question? How?

- How much would

+2×

+2× +

+ +3×

+3× cost?

cost?

- Can you find other menu choices that would be worth the same amount as in the previous question? How?

- Which desserts on the menu contain the color blue?

- Which desserts on the menu contain the color red?

- Which desserts on the menu contain the color orange?

- You have been given a gift box filled with a combination of desserts worth $15. Can you find one possible set of desserts that could be in the box?

- You have been given a gift box filled with a combination of desserts worth $33. Can you find one possible set of desserts that could be in the box?

- How many distinct permutations of desserts can you find that are worth $16? "Distinct" means "different from one another." Note that here we are talking about permutations. The permutations

+

+ and

and  +

+ are distinct. This is because when we use permutations, we care about the order in which we see the desserts. List all such permutations you can find.

are distinct. This is because when we use permutations, we care about the order in which we see the desserts. List all such permutations you can find.

- How many distinct combinations of desserts can you find that are worth $16? Note that the combinations

+

+ and

and  +

+ are not distinct. This is because when we use combinations, we do not care about the order in which we see the desserts. List all such combinations you can find.

are not distinct. This is because when we use combinations, we do not care about the order in which we see the desserts. List all such combinations you can find.

- How many distinct combinations of desserts can you find that are worth $59? List all that you can find.

- What is the way that you can make $59 with the fewest menu items? Note that 5×

counts as 5 items.

counts as 5 items.

- What is the way that you can make $59 with the fewest menu items?

- What is the way that you can make $33 with the fewest menu items?

- What is the way that you can make $120 with the fewest menu items?

- How many distinct combinations of desserts can you find that are worth $300? List all that you can find.

- What is the way that you can make $30 with the fewest different types of desserts? Note that 5×

counts as only 1 type of dessert.

counts as only 1 type of dessert.

- What is the way that you can make $72 with the fewest different types of desserts?

- What is the way that you can make $128 with the fewest different types of desserts?

- What is the way that you can make $133 with the fewest different types of desserts?

- Can you make $100 using only desserts that have blue in their image? List all such combinations.

- Can you make $75 using only menu items that have red in their image? List all such ways that you can find.

- You have been given a gift box filled with desserts worth either $116, $117, or $118. What is the fewest number of menu items that could be in the box?

- You have been given a gift box filled with desserts worth either $116, $117, or $118. What is the fewest type of desserts that could be in the box?

"GUESS AND CHECK"

Problems like these are straightforward to understand if we understand addition and multiplication; however, it is remarkably difficult to solve some of these problems. Often times, it feels that the only possible approach to this is to try several options and check each. This strategy is called "guess and check." It is straightforward to use, but it can be very slow to do. Imagine using guess and check to find how many dessert combinations could add up to $10178-- it could take a long time to get the right answer!

ACTIVITY: M&M COMBINATORICS: COMBINATIONS AND PERMUTATIONS

Combinatorics is the study of ways to count things, such as the ways to count distinct combinations and permutations of desserts on the previous page. Here we can do more combinatorics using M&Ms. Every student should be given several M&Ms (if you are in Europe, Smarties candy will do instead). Do not eat your candy until after the activity has concluded!

How many permutations can you make out of 1 red, 1 blue, and 1 green M&Ms? In permutations, order matters, so RBG is distinct from GBR. Using your M&Ms, make all permutations that you can.

How many combinations can you make out of 1 red, 1 blue, and 1 green M&Ms? In combinations, order does not matter, so RGB is not distinct from GBR? Using your M&Ms, make all combinations that you can.

How many permutations can you make out of 1 red, 1 blue, and 2 green M&Ms? Make all of them.

How many combinations can you make out of 1 red and 2 green M&Ms? Make all of them.

How many combinations can you make out of 1 red, 1 brown and 2 green M&Ms? Make all of them.

How many combinations can you make out of 1 orange, 1 blue and 2 green M&Ms? Can you find the answer without making all of them.

PERMUTATIONS ON MOVIE SEATS

Consider 4 friends that come to the cinema: Alexei, Brenda, Carmen, and Dimitri. They reserve 4 seats together in one row.

- Consider the point at which none of the friends has yet chosen a seat. How many people can choose the first seat?

- Consider the point at which only one person has chosen a seat. How many people can choose the second seat? Why?

- Consider the point at which exactly two people have chosen a seat. How many people can choose the third seat? Why?

- Consider the point at which exactly three people have chosen a seat. How many people can choose the fourth seat? Why?

RULE OF PRODUCTS

Consider a married couple, Mary and Joseph, out for dessert. Each will eat exactly one dessert. Joseph only likes Boston cream pie, cupcakes, and pumpkin pie. Mary only likes pumpkin pie, jello, birthday cake, and blueberries.

- How many different desserts interest Joseph?

- How many different desserts interest Mary?

- How many possible outcomes might be brought to the table? List them all.

Without listing all possible outcomes for both Joseph and Mary, we know that Joseph considers 3 desserts and Mary considers 4 desserts. Because their orders do not influence one another (we say that they are "independent"), each choice of Joseph's can be paired with every choice of Mary's. This pairing is called the "Cartesian product" of their possible choices. In this case, the total number of outcomes will be 3×4=12. Check this against your answers above.

FACTORIAL: PERMUTATIONS ON MOVIE SEATS REVISITED

If 5 people are choosing from movie seats, then the first seat could be occupied by any one of the 5 people. Hence there are 5 choices for the first seat. There are only 4 choices for the second seat: this is because whoever sat in the first seat cannot also sit in the second seat (after all, they are only one person!). The 5 choices for the first seat and the 4 choices for the second seat can influence one another in this way; however, the number of choices is independent of who sat down first. Hence, we can use the rule of products to find 5×4=20 choices for the first two seats. If we continue in this manner, we have 5×4×3×2×1=120 choices for 5 friends choosing seats at the cinema. We will use the shorthand 5! for this.

CODE: FACTORIAL

We can compute n! using a product within a loop in python:

- How many distinct permutations come from 6 friends choosing seats at the cinema? Edit the python code above to find the answer.

- How many distinct permutations come from 10 friends choosing seats at the cinema?

CODE: RECURSION

Notice that both 5!=5×4×3×2×1 and 4!=4×3×2×1 contain 4×3×2×1; therefore, 5!=5×4!

This notion can be useful for "recursion" a process by which a function actually calls itself to get a job done! Every recursive function must contain a "base case," which ensures that the function does not keep calling itself forever.

- Remove the base case from our recursive factorial function. What happens?

CODE: MORE ADVANCED RECURSION

We can use recursion to make code that is very clean and easy to read. Consider this incomplete function to sort a list. The approach is to sort the first and second halves of the list and then merge the sorted results together. We can merge sorted lists into a new sorted list by taking the next value in each list

- Consider a list x=[1,5,8,9]. What is x[:2]? What is x[2:]?

- What does x.append(10) do?

- What does x.extend([12,15,21]) do? Can you do this with multiple calls to x.append instead?

- Our sorted_list function is still incomplete-- it needs some way to sort the first and second halves of the list. Can you use recursion to sort the first and second halves and complete our function?

CODE: RULE OF DIVISION: BINOMIAL AND MULTINOMIAL

Consider 2 red and 3 green M&Ms.

- How many total M&Ms are there?

- How many permutations are there for ordering all of these M&Ms? Pretend each M&M is a person choosing a movie seat.

- Now consider combinations on the M&Ms. Let's name the 3 red M&Ms "g1", "g2", and "g3". For combinations, we do not distinguish between a b and b a. How many ways are there to order the 2 red M&Ms using permutations? Consider this as 3 green M&Ms choosing movie seats.

- For combinations, we care about neither the different ways to arrange the red M&Ms nor the different ways to arrange the green M&Ms. The rule of division is the corollary to the rule of products: When we compute the number of permutations on the 2 red and 3 green M&Ms, we count each ordering of the red M&Ms as distinct and each ordering of the green M&Ms as distinct. In order to compute the number of combinations, we need to divide the number of permutations on all M&Ms by the product of the number of permutations on red M&Ms and the number of permutations on green M&Ms. This is known as the rule of division. Write out all distinct combinations on 2 red and 3 green M&Ms. Compute the number of combinations using the rule of divisions. Do you produce the same answer?

For 2 M&M colors in the example above, this results in a "binomial": the number of distinct combinations is 5! / (2!×3!). We can compute this in python:

The binomial is named because it is the resulting coefficients when expanding the two-term polynomial (i.e., the "binomial") (a+b)n. For example, (a+b)^3 = (a^2+2ab+b^2)×(a+b) = a^3+3a^2b+3ab^2+b^3. The coefficients [1,3,3,1] can be found using these binomials: 3!/(3!0!), 3!/(2!1!), 3!/(1!2!), 3!/(1!3!).

Interestingly, we can get the binomial coefficients from Pascal's triange. In Pascal's triangle, a number gets the sum of the numbers above it:.

For more than 2 M&M colors, this results in a "multinomial." We can use the rule of division to compute the number of combinations for 2 red, 3 green, and 2 blue M&Ms.

CODE: COMPUTING ALL COMBINATIONS

Consider 4 orange, 2 brown, and 3 blue M&Ms. For a fixed problem like this, we can write code to compute all combinations using loops:

We can do this with yield and, in a case where we don't need all the combinations, avoid computing them all:ACTIVITY: M&M COMBINATORICS: SUBSET-SUM AND KNAPSACK

Every student should be given a handful of M&Ms (roughly 4 fun-size packs). Pretend that each color of M&M has a different mass:

Part 1

| M&M color | Mass |

|---|---|

| RED | 2 |

| ORANGE | 5 |

| YELLOW | 7 |

| GREEN | 10 |

| BLUE | 11 |

| BROWN | 13 |

Given a set of numbers (here, the M&M masses), a "subset-sum" problem asks if it's possible to make a target value by summing members of the set. This problem is famously tricky!

- What is the total mass of RED + ORANGE + BROWN?

- What is the total mass of 2×RED + 3×GREEN + BLUE?

- Is there another way that you can make a total mass of 45?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find a total mass of 32?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find a total mass of 64?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most ways to reach total mass 74?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most ways to reach total mass 103?

- Using your M&Ms, who can reach mass 52 using the fewest M&Ms possible?

- Using your M&Ms, who can reach mass 65 using the fewest M&Ms possible?

- Who can reach mass 30 using the fewest BROWN M&Ms? To break ties, the solution with fewest total M&Ms used wins.

- Who can reach mass 26 using the fewest BROWN M&Ms? To break ties, the solution with fewest total M&Ms used wins.

- Can you reach mass 61 using every color of M&M at least once?

Part 2

| M&M color | Mass | Value |

|---|---|---|

| RED | 2 | 3 |

| ORANGE | 5 | 6 |

| YELLOW | 7 | 8 |

| GREEN | 10 | 4 |

| BLUE | 11 | 9 |

| BROWN | 13 | 2 |

Given a set of masses and paired values, a "knapsack" problem asks for the most valuable solutions that could be held in a knapsack (i.e., with a given total mass). This problem is slightly more difficult than subset-sum.

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most valuable way to make a total mass of 60?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most valuable way to make a total mass of 44?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most valuable way to make a total mass of 70?

- Using your M&Ms, who can find the most valuable way to make a total mass of at most 60?

- BLUE is the most valuable color. Would a valuable solution with a small total mass use many BLUE M&Ms? Why or why not? What is the best color of M&M to use man of if possible? For this question, consider which you'd rather have: a barrel filled with pennies, a barrel filled with nickels, a barrel filled with dimes, or a barrel filled with quarters. On one hand, quarters are the most valuable, but they also take the most space, so fewer fit in the barrel. On the other hand, dimes are the smallest, and so many fit in the barrel; dimes have a moderate value. The best ratio of value to size is found with dimes, not quarters.

CODE: SUBSET-SUM AND KNAPSACK

We can solve the subset-sum problem by using brute force to iterate over the combinations:

We can use the same approach to solve the knapsack problem:

If we wanted to solve the knapsack problem more efficiently, we could start with configurations that have a large quantity in the highest value-to-mass ratio.

CODE: SUBSET-SUM WITH DYNAMIC PROGRAMMING

We can add all possible contributions from a color one at a time, keeping track of every solution thus far. This process is called "dynamic programming."

If we only need one arbitrary answer of the many possible ways to reach the goal mass, we can use a faster, alternative solution:

- Use the dynamic programming code above to redo some of the questions from ACTIVITY: M&M COMBINATORICS: SUBSET-SUM AND KNAPSACK. Can you find any better answers with the help of the computer?

MASS SPECTROMETRY

We've seen that if we can accurately measure the mass of something, we can often determine what it is. Measuring the mass of a few atoms isn't easy: after all, individual atoms are so small that your bathroom scale won't accurately register their weight.

Mass spectrometry is a field of study where scientists estimate the masses of atoms and compounds in a sample.

MASS SPECTROMETRY WITH BOATS

Consider a rough sea with waves that alternately push left and right. Small boats are pushed more by the waves, but the waves move large boats less. As water streams downhill away from the rocks, both small boats and large boats are pulled out to sea. Gravity keeps the large boats safe by pulling them away from the rocks; however, a small boat would be hit by a wave and knocked uphill, crashing it into the rocks:

If water streams downhill toward the rocks, both small boats and large boats are pulled into danger. But when the small boat is pulled close to the rocks, a wave going away from the rocks will push it back out to sea; however, a large boat, being too big to be effected much by waves, would pulled downhill, crashing it into the rocks:

Elements and compounds in mass spectrometry behave in the same way: We can construct experiments to crash small elements and compounds and we can construct experiments to crash large elements and compounds. In this manner, we can filter elements and compounds by mass, only allowing the elements and compounds that we want to pass through.

- With the boats, can you think of a two-stage experiment that would only allow medium sized boats to survive?

MASS SPECTROMETRY WITH CHARGED QUADRAPOLES

Mass spectrometrists don't really use boats; however, they do use pairs of electrically charged metal poles, which behave in the same manner. If we steal electrons from the elements and compounds so that they become positive ions and then we feed a negative electrical charge to the metal poles, the ions will become attracted to the poles. Small ions, having less inertia from their lower mass, will quickly be pulled toward the poles and crash into them. Large ions, having more inertia from their higher mass, will take more time to be pulled toward the poles and crash into them. Regardless of their mass, all elements and compounds that collide with the poles will lose their charge and cease to be counted in the experiment.

On the other hand, if we use electricity to give the pair of poles positive charge, then they will repel the positive ions. Both low-mass and high-mass ions will be safely shepherded through the poles.

So far the attraction to or repulsion from the poles has been like the gravity for the boats: it has affected large and small masses similarly. But consider what will happen if we oscillate the charge across the poles: When the poles are mostly positive, both ions will usually be repelled and kept safe; however, the oscillation, like the waves on the small boat, will push the small ions around roughly. When the small ions collide with the poles, they will be lost. This setup eliminates low-mass ions and allows high-mass ions to pass through.

On the other hand, if the poles are mostly negative, they will attract both ions, pulling them into danger; however, the oscillation, like the waves on the large boat, will steadily pull the larger ions toward the poles, while the smaller ions will be rescued and pushed away by the oscillating charge. This setup eliminates high-mass ions and allows low-mass ions to pass through.

We can use two pairs of poles at a time. This allows us to

eliminate masses that are too low and to eliminate masses that

are too high. In this manner, we can filter and only allow a

chosen range of masses to pass through. These pairs of poles

are arranged in a square in space, and are called a

"quadrupole." The up-down plane can be responsible to crash

ions that are too small, while the left-right plane can crash

ions that are too large. Instead of simply wandering left and

right or up and down, ions will actually pass through the

poles in spirals:

- How would you use a quadrupole to allow only ions of medium mass to pass through?

EXERCISE: FILTERING BY MASS

- These elements and compounds try to get into the carnival

in order to ride the ferris

wheel:

Fe1 ,Al1 ,H2 ,O2 U1 ,As1 ,Ti1 ,H2O1 ,H2S1O4 ,Ar , andN1H3 . If the security gate at the carnival entrance allows all elements and compounds with masses ≤60u, then which elements and compounds will be allowed into the carnival? - If the ferris wheel only allows masses ≥30u, then which elements and compounds that were allowed inside the carnival would also be allowed on the ferris wheel?

- Choose the mass threshold for the security gate and the mass threshold for the ferris wheel so that the number of elements/compounds denied entry to the carnival, number of elements/compounds denied access to the ferris wheel, and number of elements/compounds allowed into the carnival and allowed on the ferris wheel are roughly the same.

TIME OF FLIGHT: MASS SPECTROMETRY BY RACING ELEMENTS

A second means of performing mass spectrometry is done by racing elements and compounds. Consider ions of different masses, large to small. The ions are released into an electric field such that they are repulsed from the starting line and attracted to the finish line.

The force of the electric field on all of the ions is the

same; however, smaller ions, which have lower mass, will

experience greater acceleration from the same force. These small

ions will reach the finish line first. On the other end of the

spectrum, large ions will take a long time to finish the race.

This type of mass spectrometry is called "time of flight." It not only sorts the ions by mass, it can also be used to find out the abundance of ions at different masses: Using physics, we can solve for the formula that tells us when different masses should arrive at the finish line; conversely, we can use the finishing time to determine an ion's mass. Also, using a metal cup (called a "Faraday cup") at the finish line, we can quantify how many ions of each mass have arrived. As a result, we produce a "mass spectrum" that tells us the abundances of ions at every mass:

ACTIVITY: TIME OF FLIGHT

Have students cary a heavy object, a medium-weight object, and a light object. Time the students as they run a fixed distance. From the times, see if other students can figure out which object the student was carrying each time.

MASS SPECTROMETRY BY ORBITING WITH A JUMP ROPE

Another approach used for mass spectrometry is to pull ions into orbit. You can visualize this by imagining a girl spinning with a jump rope tied around a tennis ball. She can spin the tennis ball around herself many times a minute.

But if the girl tries to pull a bowling ball toward herself with the jump rope, it will be far heavier. Its orbit will be much larger, and if the speed is the same, then it will take a much longer time to perform one revolution around the girl. Thus the bowling ball will only orbit her a few times a minute.

If we can only measure the number of times a ball revolves around the girl in a minute, we can use that to estimate the mass of the ball: a high-mass ball will revolve around her only a few times in a minute, a low-mass ball will revolve around her many times in a minute, and a medium-mass ball will revolve around her an amount in between.

This principal is the basis of FT mass spectrometry. The FT stands for "Fourier transform." We do not use jump ropes and balls, but instead pull ions toward the center with massive a superconducting magnet. We do not count the number of revolutions by eye, but instead count them by allowing the charged ions to induce a current in wires around which they are orbiting. The result gives us the frequencies of revolutions around the wires. We can measure several ions simultaneously by measuing the frequencies of currents induced in the wires. In turn, we can map these frequencies to the correct masses that would produce them using something called a Fourier transform. This is where the name of this type of mass spectrometry comes from.

FT mass spectrometry is extremely precise: it can not only measure the dust on a fly's wings, it can measure the mass defects in different compounds. This precision allows us to figure out not only what atoms are in a compound, but also how they are bonded to one another. This helps us determine the chemical structure of a compound.

FT mass spectrometers are very large and expensive. They also require liquid helium (which is far colder than liquid nitrogen) to operate. For this reason, they are not only high quality, but also difficult to purchase and use. As a result, a cheaper alternative was invented: the Orbitrap mass spectrometer uses the same principle but by using electric field rather than magnetic field. This greatly simplifies some of the instrument, eliminating the need for the large superconducting magnet and for its liquid helium cooling; however, this also presents an additional challege: since we are using electric field to attract the ions, we cannot directly measure electrically induced current in the wires around which it is orbiting, because we would measure the electric current we are using to attract the ions. As a result, Orbitraps do not measure the current of the revolving rings of ions; instead, they measure the oscillations as those rings glide up and down over two halves of the detector. This process is very subtle and was difficult to invent.

ACTIVITY: COUNTING FT ORBITS

On a merry-go-round, have each student push it around as fast as they can. Other students will count the revolutions in a fixed period of time (e.g., one minute). Repeat this process with a varying number of adults on the merry-go-round. From the number of orbits, can students identify how many adults were on the merry-go-round?

ACTIVITY: PANNING FOR SAND

With students, fill a plastic bowl with water. Sprinkle a pinch of sand into it. Outside or over a basin, gently agitate the bowl in a circle so that the water forms a small whirlpool. Where does the sand go? Where does the water go? Which has greater density, sand or water? Why?

- If a car stops abruptly and a boy in the car is drinking a glass of water with no lid on it, where will the water spill? Consider, which is denser, the water in the cup or the air in the car that it would displace?

- If a car stops abruptly and a boy in the car is holding a helium balloon, where will balloon go? Consider, which is denser, the helium in the balloon or the air in the car?

ACTIVITY: FILTER PAPER CHROMATOGRAPHY

Each student is given a strip of coffee filter, which has been

cut into a thin strip. The student will write their name on

the coffee filter in pencil, and then make a thin band of

Sharpie marker (any color) an inch up the filter

paper.

The instructor will pour rubbing alcohol into a cup. The

rubbing alcohol should be less than 1 inch high, so that it

doesn't directly touch the Sharpie bands. Paperclip each

student's filter paper to the rim of the cup so that the

Sharpie band is low in the cup but not directly touching

the rubbing alcohol.

As the rubbing alcohol travels up the filter paper, it carries

with it some pigment from the Sharpie marker. Even if the

marker has only one visible color, it may be composed of

several distinct pigments. Some pigments will travel more

slowly through the filter paper, while others travel more

easily on the rubbing alcohol.

- Think of the time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer. Why might some pigments in the Sharpie marker travel further up the filter paper?

- Would you guess that the larger pigments would travel more easily through the filter paper or that the smaller pigments would travel more easily through the filter paper? What does that mean about the masses of the pigments that have been carried through the filter paper?

FRAGMENTATION SPECTRA AND LINEAR MOLECULES

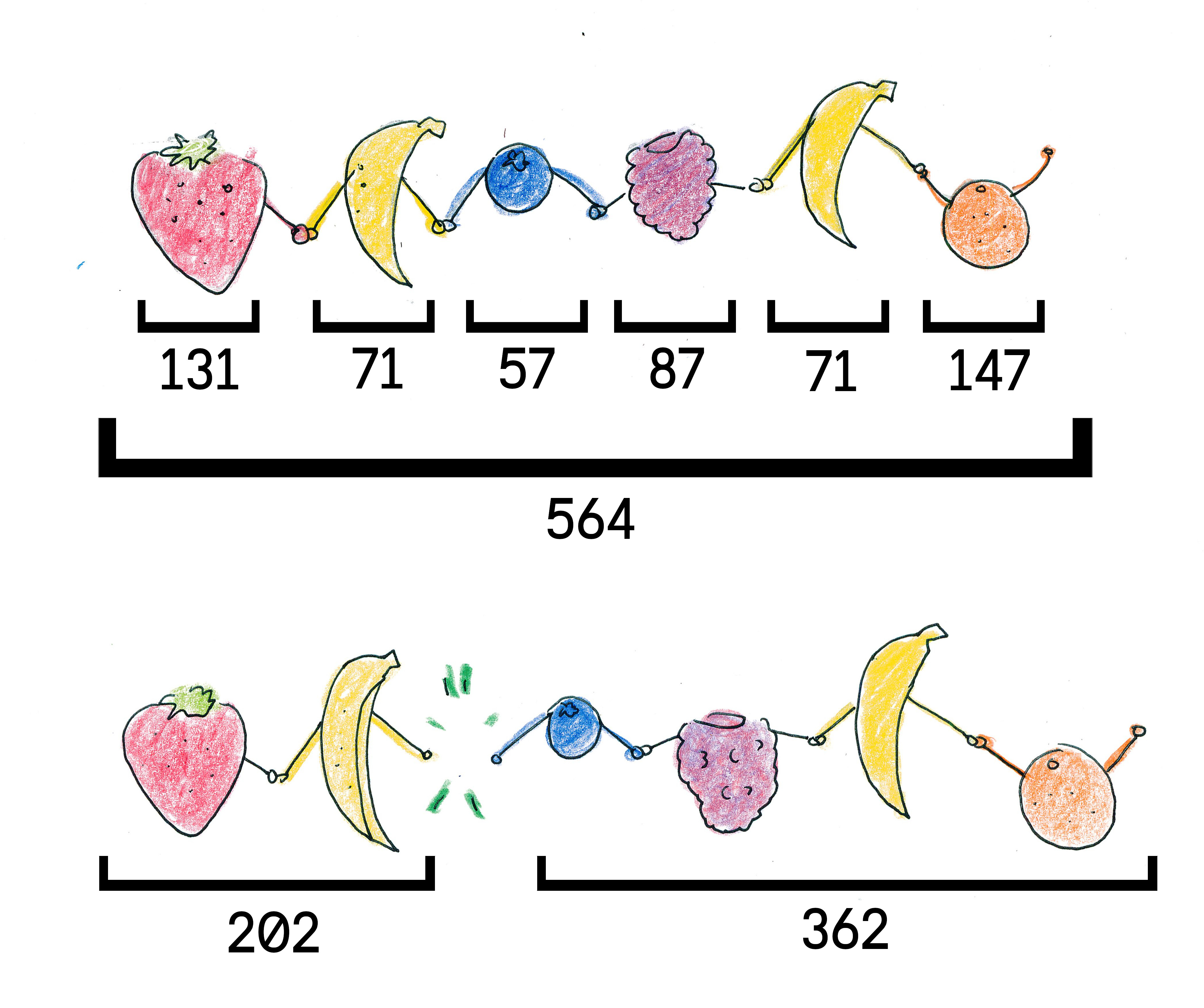

Sometimes molecules build linear chains, like children holding hands as they cross the street. When this happens, the mass spectrometer measures the total mass of all pieces in the molecule.

But sometimes the chain breaks in one place. When this happens, the mass spectrometer measures the mass of the first half and the mass of the second half.

If the chains break exactly once in each location, then a fragmentation mass spectrum will be produced, such as the following:

- Can you find the sequence of fruits that would produce the above fragmentation mass spectrum? This process is called de novo sequencing.

ACTIVITY: FRAGMENTATION SPECTRA

Assign each student a random number using the following code:

Write the students' values by the names on the board.

Bunch several students together (but not all students). Students not part of the bunch will look on and solve the puzzle. Compute the total of the students in the group and write it on the board. Choose one student to leave the bunch, without the knowledge of the students looking on. Compute the new total without the student chosen to leave the bunch. Tell the new total to the students looking on-- can they figure out which student has been chosen to leave the bunch?

Repeat this process until the bunch has only one student remaining.

ACTIVITY: 3SUM

Assign students random numbers using the following code:

Have each student write their number on a sheet of paper. The students will mill around, meeting in groups of size 3. If the sum of two people's numbers is the third person's number, the group wins. If the number of students is not a multiple of 3, then have teachers join so that the number of players is a multiple of 3.

This famous problem is called the "3SUM" problem.

ACTIVITY: 3PROD

Assign students random numbers using the following code:

Have each student write their number on a sheet of paper. The students will mill around, meeting in groups of size 3. If the product of two people's numbers is the third person's number, the group wins. If the number of students is not a multiple of 3, then have teachers join so that the number of players is a multiple of 3.

Is this more or less difficult than the 3SUM activity?

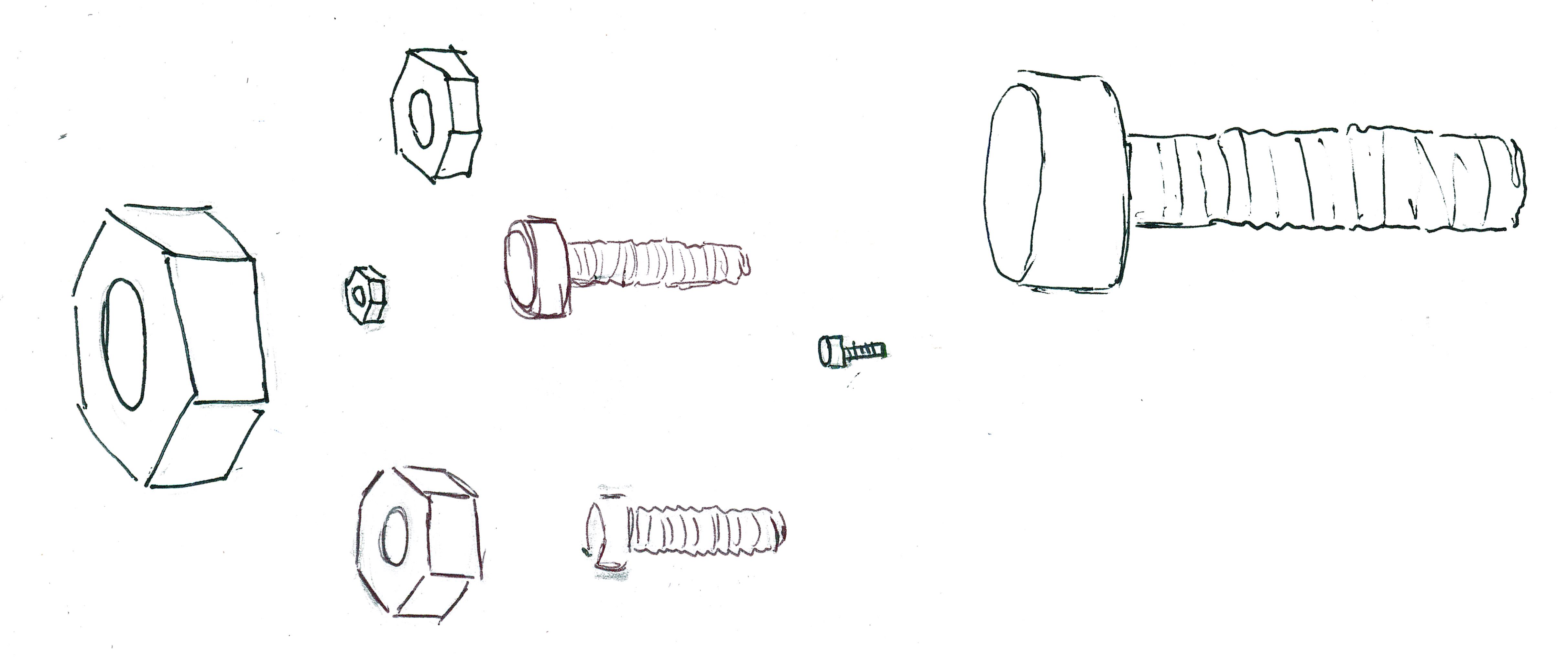

ALGORITHMS AND FINDING THE NUT THAT MATCHES A BOLT

An "algorithm" is a kind of recipe, a step-by-step bunch of instructions. Let's think about algorithms for pairing nuts and bolts.

Consider a pile of bolts and a pile of hex nuts. Each bolt is the right size for exactly one nut and each nut is the right size for exactly one bolt.

In about one second, we can compare a nut to a bolt to see if the fit is too tight, too loose, or a perfect fit, but we cannot easily compare two hex nuts to one another or compare two bolts to one another. Can we construct an algorithm that will pair every hex nut and bolts?

ACTIVITY: FINDING MATCHING NUTS AND BOLTS

Assemble a pile of hex nuts and a pile of bolts that fit one another. Pile them unpaired, and have students try to pair them up as fast as possible. Keep a list of times. The student with the best time wins.

ALGORITHMS: FINDING MATCHING NUTS AND BOLTS

One easy algorithm for pairing the hex nuts and bolts would simply try every hex nut with every bolt. If we have 10 hex nuts and 10 bolts, this will try 10×10 pairings and take roughly 100 seconds. And, more generally, if we have n hex nuts and n bolts, there will be n2 pairings and will take roughly n2 seconds.

This may be alright when we have n=5 or n=10; however, when n=1000, this will take a million seconds or over 11 and a half days.

ACTIVITY: FINDING A WORD IN THE DICTIONARY

It turns out that trying every hex nut with every bolt is unnecessarily time consuming. To be more efficient, we'll need to avoid trying every pairing.

If you were looking up a word a dictionary book, would you start at the first word and continue on one at a time? That would be similarly inefficient. Instead, you might try opening the dictionary halfway and then deciding if the word is in the left half or the right half.

For this activity, have two dictionary books. Pairs of students will be given obscure words chosen in advance. The first student to give the definition wins and stays standing, while the slower student is replaced by another from the crowd. Either continue until each student has had a chance or proceed tournament style, facing off pairs until one student wins.

ALGORITHMS: LOOKING UP A WORD IN THE DICTIONARY

If we have n words in the dictionary, opening to halfway will allow us to determine whether the word is in the left half or the right half. Once we determine the correct half of the dictionary, we have n/2 words to consider. We can open halfway to that half and determine whether or not the word is in the first half of the remaining words or the second half of the remaining words. This will narrow the words to n/4 candidates.

We can continue in this manner until we get to the correct page, and then continue dividing the page in half until only one word remains.

How long will our algorithm take? Well, let's consider how many times we need to divide by 2 in order to narrow our search to only 1 word: If we have n=1024 words, we can divide in half to 512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, meaning we need to divide in half 10 times; another way to say this is that 210=1024. If we have n of 1 million words, we need to divide in half around 20 times, because 220>1 million. In general, if we want to find out how many times we need to divide n in half in order to get 1 answer, we need to solve 2i=n for the variable i. This will give us the number of times we need to divide in half.

The solution to this equation is given by something called a "logarithm": i = log2(n).

If we are able to user our intuition about a word to jump directly to a page very close to the correct page, this is reminiscent of a "hash." With a hash, our brains (or a computer) essentially asks several yes/no questions simultanouesly instead of asking the left/right (which are like yes/no) questions one at a time.

Because exponential growth is so fast, it turns out that the number of particles in the univers can be given by roughly 2270. That means that the log of the number of particles in the universe is 270, meaning we need only 270 strategically chosen yes/no questions to pick one out of all of the particles in the universe.

ALGORITHMS: FINDING MATCHING NUTS AND BOLTS

How can we use what we learned about logarithms to help us pair the hex nuts and bolts?

If we choose a hex nut at random, we can try it with every bolt, and use it to make three piles of bolts: bolts that are too large, bolts that are too small, and the bolt that fit perfectly. If we use the bolt that fit perfectly, we can try it with every hex nut, thereby separating the hex nuts into three piles: the hex nuts that are too large, the hex nuts that are too small, and the hex nut that fits (which is the random hex nut we started with).

Notice that we only need to try pairing the pile of too-big hex nuts with the pile of too-big bolts and pairing the pile of too-small hex nuts with the pile of too-small bolts.

On average, the random hex nut we chose will be roughly the middle one. That means that the pile of hex nuts that are too big will have roughly n/2 hex nuts and the pile of hex nuts that are too small will have roughly n/2 hex nuts. Likewise, the piles of bolts that are too big will have n/2 bolts and the pile of bolts that are too small will have n/2 bolts.

This means that we will roughly divide the piles in half log2(n) times before we have only one hex nut and one bolt (which must match). Each time we divide in half, we try every hex nut and every bolt considered. Thus, the overall time it will take will be n log2(n).

Consider what happened with our simple try-ever-pair algorithm when we had one million hex nuts and bolts: n2 will be 1012 or one trillion comparisons. If each took us one second, that would take us around 31 thousand years.

Using our new dividing-in-half strategy, pairing one million hex nuts and bolts would take us roughly 230 days.

ACTIVITY: FINDING MATCHING NUTS AND BOLTS (REVISITED)

Have students try acting out the dividing-in-half strategy to pair the nuts and bolts.

ACTIVITY: LIVE GUESS WHO

Have a population of students and adults where one is chosen, secretly at random. A separate student will ask yes/no questions of the population (e.g., is the person wearing glasses? is the person a boy or a girl?). How many questions can be used to find the correct person? What strategy is best in the worst-case scenario to determine the correct person?

ACTIVITY: TOWER OF HANOI

The Tower of Hanoi is a puzzle where only smaller tiles can be stacked on top of larger tiles. The instructor will cut 8 pieces of wood or foam in squares of different sizes beforehand. Mark 3 Xs on the ground using blue or gray tape.

Stack the tiles on top of one of the taped Xs with the larger tiles on the bottom. Have students attempt to move the entire stack to another X. Tiles can only be stacked with smaller tiles on top of larger tiles.

If this is tricky, start with a stack of only 4 tiles.

- Time the students moving the stacks from one X to another: who can move the pile the fastest without breaking the rule that only smaller tiles can be stacked on top of larger tiles?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 3 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 4 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 5 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 6 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 7 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of 8 tiles from one X to another X?

- How many steps are needed to move a stack of n tiles from one X to another X?

CODE: SIMPLE 3SUM

Like with the hex nuts and bolts, we can solve 3SUM in n3 steps by trying all a,b,c combinations.

CODE: 3SUM BY SORTING

Using our hex nuts and bolts as inspiration, we can solve 3SUM in n2log(n) steps by trying all a,b combinations and querying if a+b is in the sorted set.

CODE: 3SUM BY HASHING

We can solve 3SUM in n2 steps by trying all a,b combinations and querying if a+b is in the set. This uses hashing, which is reminiscent of trying to use our intuition to jump directly to the location of a word in the dictionary.

ISOTOPES AND ABUNDANCES

Isotopes have different natural frequencies with which they appear in nature. For example, we saw that the most common isotope of silver has 60 neutrons, has a mass of roughly 106.905097u and occurs roughly 51.8% of the time, while the second most common isotope of silver has 62 neutrons, has a mass of roughly 108.904752u, and occurs roughly 48.2% of the time.

Consider

- Without trying all pairs of isotopes, can you find the

most frequent/abundant isotope of

K1Cl1 ? What is its mass? How frequently does it occur?

We can use python's itertools.product to try all masses and

abundances with which

ALGORITHMS: FINDING THE k CHEAPEST MEALS AT A RESTAURANT

Consider a restaurant menu with n foods and n drinks listed on the menu. Consider a meal as any pairing between a food and a drink.

We can find the cheapest meal easily: it is the cheapest food with the cheapest drink. But how can we find the cheapest 3 meals? How can we find the cheapest 10 meals? And how can we find the cheapest k meals?

The naive approach to this problem is like the pairing of hex nuts and bolts: We simply try all foods with all drinks to produce n2 pairings, and sort them in n2log(n) time. Then we find the best k results from the sorted list.

A more efficient approach would be to sort the foods cheapest first and sort the drinks cheapest first and to make a grid out of them (with foods labeling rows and drinks labeling columns). The top-left corner will be the cheapest meal. We can use the fact that any cell in the grid will be cheaper than its right neighbor and cheaper than its lower neighbor; therefore, only consider the right neighbor and lower neighbor of a cell after the cell was chosen. At any given moment, there will be several cells under consideration.

Thus, at each iteration, choose the most abundant isotope currently under consideration (starting with the top-left corner). Mark it as used and add it to the list of results. Now mark both its right and lower neighbors as under consideration.

- How does finding the k cheapest meals at a restaurant

relate to finding the k most abundant isotopes

of

K1Cl1 ?

ACTIVITY: FINDING THE k CHEAPEST MEALS AT A RESTAURANT

Using a real restaurant menu, have students find the cheapest 30 meals. Choose a menu in advance that has several food options with distinct prices and several drink options with distinct prices.

First, have the students find these meals by adapting the python code using itertools.product.

Second, have the students find them by hand by constructing a grid as described above.

THE MULTINOMIAL AND ISOTOPES OF COMPOUNDS

Consider water,

Try pairing hydrogen with hydrogen using the

itertools.product code. What are the most abundant isotopes

of

It turns out these follow a binomial, because every pairing (a,b) can be rewritten as (b,a) as long as a≠b. This can be thought of as the expansion of the polynomial (0.99972x1.007825031898 + 0.00001x2.014101777844)2. Notice that when we compute terms of this polynomial, we multiply the frequencies and add the masses, just as we should.

Can you construct the most abundant isotopes

of

If we use A to denote the most abundant isotope of hydrogen and B to denote the second most abundant isotope of hydrogen, there is 1 way to use only the most common isotopes of hydrogen: AAAA. But there are 4 ways to use 3As and 4Bs: AAAB, AABA, ABAA, BAAA. These numbers of ways correspond to the configurations that have identical masses (and which we will merge together).

When an element has more than two commonly observed isotope states, then the polynomial expansion will use a multinomial instead of a binomial to find the number of ways things can occur. For example, if we have isotopes A, B, and C, there is only one way to choose 4As; however, there are several ways to choose 2As, 1B, and 1C. The number of ways is found in the multinomial, which we described previously.

- How many commonly found isotopes does

Xe have? - How would you find the isotopes of the imaginary compound

Xe4 ? What polynomial would you make? - Use the multinomial expansion of that polynomial to find

all isotopes of

Xe4 .

GENERATING FUNCTIONS

Storing information inside polynomials in the manner we saw above is very powerful. A more advanced version of this uses polynomials that continue infinitely: these are called "generating functions.".

Consider the polynomial 1 + x + x2 + x3 + ...

First let x=1/2. What is the sum? We can begin by approximating the sum with only partial sums, which leave out many small terms: First, we could simply use the 1. Second, we could use 1+x=1.5. Third, we could use 1+x+x2=1.75. Consider what happens as we proceed in this manner: We will become closer and closer to 2, but we will never pass 2. Why? Because when we approximate using 1, we have 1 leftover from 2. When we approximate using 1.5, we have 1+x=1.5 leftover from 2. When we approximate using 1+x+x2=1.75, we have 0.25 leftover from 2. That means that as we make our approximation more and more exact, the difference between 2 and our approximation becomes exponentially smaller: 1, then 1/2, then 1/4, then 1/8, and so on. As we become more and more exact, this difference will become infinitesimal, meaning the exact value is 2.

We can see this more generally by using algebra: Let's name

our answer a=1+x+x2+x3+...

What happens if we multiply a⋅x? We shift every term in a to a greater power of x:

a⋅x=x+x2+x3+x4+...

Do you see how similar this is to the original sum? If we add 1, we will get the original sum!

1+a⋅x=1+x+x2+x3+x4+...=a

Using this, we can solve for a:

1+a⋅x = a

1 = a - a⋅x

1 = a⋅(1-x)

a = 1/(1-x).

We can check this against our solution from x=1/2: 1/(1-1/2) = 1/(1/2) = 2.

This means that if we ever want to use the polynomial 1+x+x2+x3+... to hold values each having masses of 1 and abundances of 0,1,2,3,... we can try all pairings by doing (1+x+x2+x3+...)⋅(1+x+x2+x3+...) = 1/(1-x)⋅1/(1-x). We would say that 1/(1-x)2 is the generating function for the infinite polynomial we wanted here.

- How are isotope masses and abundances encoded into a polynomial?

- Use python to sum the first 100 terms of the geometric series with x=1/3. How does the answer compare to the closed form for a that we found above?

- How are the polynomials from two different elements' isotopes used together to try all pairings?

- What is a generating function? Why would it be used? Why not simply work with the polynomial directly?